For many years, I’ve been in the habit of reading fiction in Spanish, English, and my native language regularly. And sometimes rereading, naturally.

A little over a year ago, I reread Gogol's The Coat.

"In the department of… but it is better not to name the department".

And I could no longer tear myself away from the life story of a little man in an old overcoat. A story that once again evoked a stream of feelings and thoughts that lie beyond words and that can only be expressed with a smile or a tear.

And how, it occurred to me, might all this sound in English?

Today, we need only wish – click! and the material is already in front of our eyes. And there is absolutely no need to waste time going to a library of foreign literature. So, soon, there were different translations of the story to hand. Four of them! Which, in fact, is not surprising. Many literary works are translated into the same foreign language several times. Especially the classics. For example, The Prince and the Pauper by M. Twain was translated into Russian four times, Madame Bovary by G. Flaubert seven times, and Vanity Fair by W. Thackeray eleven times! There are many examples. Top of the leaderboard, with countless translations of his plays, is our dear William Shakespeare.

So it would be impossible for Gogol's The Coat to escape the notice of translators. No wonder Vladimir Nabokov called it the best Russian story ever written. With quadrupled interest, I began to read my colleagues’ work.

All options were good, each in their own way. They differed in terms of the level of translation skills, but all seemed to be similar in one respect – their aim to inform prevailed over their aim to express. In other words, they introduced the reader to the content of the original but didn’t always convey its aesthetic features.

This story is distinguished by the specific intonation and charm of the speech of its characters. We have the rough vulgarity of the watchman’s delivery, the good-natured vernacular of the tailor, and the night robbers’ uncivil treatment of their victims. And, of course, the protagonist's utterances and reflections, perpetually sprinkled with his filler words, with which he sometimes simply gushes. And we also have the inanimate hero of the story – the old coat! It has two different names, the noble and the derogatory. And with both of them, it walks through from the beginning of the story to its very end, creating a subtle thread for the reader to follow.

In my subjective opinion, each of the translators coped with the task satisfactorily. But, I repeat, with a focus on content, while the emotional aspect of the work took somewhat of a back seat. This is often explained by the specifics of Gogol's style, which were described by one American critic* as a "translator's nightmare". But there also exists another, and no less significant, factor.

Literary translation must is considered an art and, like any art form, is developed, changed and improved, passing through certain stages. During the period from the middle of the 19th century almost up until the middle of the 20th century, the English translation school was focused only on familiarising the readership with foreign works of fiction, with content being the main focus. But if we take note of when these translations appeared, it becomes clear that all of them are a product of their time.

This, probably, is the reason for the characters’ speech being much closer to the literary norm in two of the earlier works by famous translators, Isabel Florence Hapgood from the USA and Constance Garnett from the UK.

It should be noted that there are translations which deviate significantly from the original, which is not necessarily due to a difficulty in understanding the text. This kind of translation technique is used when a translator, based on the plot, doesn’t preserve the stylistic characteristics of the original but writes their own work on it, creating a kind of remake. This kind of a technique can be seen in the work of Claude Field.

The latest translation of our story, published in 1960 in the USA, seems to be the most balanced among the four in terms of the content and the form. The translator's name is not listed, unfortunately.

Remarkable translations for their time. But today it is important not only to acquaint the reader with the content of the work, but also to convey its colour and spirit. The task of the translator, taking cue from the author, is to open the way for the natural, living speech of the target language and thus to convey the expressiveness of the original in the translated work. Greater flexibility of syntax and the avoidance of bookishness allow for a more accurate transfer of author's style.

In the art of translation, different types of texts require different approaches. Translation of scientific and technical literature, both direct and reverse, can be done by any competent specialist, because the main thing here is accuracy with no emotions – it doesn’t matter whether engines cry or sing. Journalistic texts require more experience, but here it is not necessary to be a native speaker either. But literary translation is another thing. This kind of work is performed by translators for whom the target language is native.

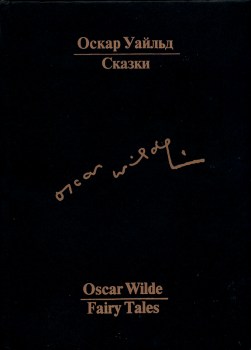

Recently, Stanitsa Publishers has launched a new series of bilingual books ''Language Through Reading''. This series is similar to the ''English for Pleasure'' series, well-known to our readers, where each book presents the work of an English-speaking author in parallel with its literary translation into Russian. In the new series, the source text is the work of a Russian-speaking author. The English translation of the first book in the new series was done by London-based translator Enya Lennon. And she did it brilliantly.

I think it's easy to guess what proposal I made to Miss Lennon.

пт, 9 апр. 2021 г., 15:46

Привет, Энья!

<…..>

Сейчас работаю над вторым изданием словаря английских омонимов.

<….>

А в планах… <….>. И это Николай Гоголь – «Шинель». Почему Гоголь? Здесь я хотел бы немного подробнее.

<….>

Соглашайся!

Юрий

In these fast-paced times, we have unprecedented technical capabilities. Soon, I received a reply from London.

пт, 9 апр. 2021 г., 20:17

Hi Yuri!

I’ve never read Шинель so I’m going to have to go and read it! I’ve been making an attempt to read more Russian classics in the last year… <….> to any Gogol yet.

<….>

I studied Constance Garnett a little at university when comparing translations because, as you say, <….>. It’s amazing… <….>! I…<….> – Eugene Onegin is a really interesting one for that!

<….>

I really like translating poetry in my free time as a creative exercise.

<….>

Your proposal sounds great!

<….>

Best wishes,

Enya

A year has flown by. A real journey through the time, space and fate of the work. And now meet a brand new translation of "The Coat" by Nikolai Gogol.

One of the important aspects in it is that Gogol's characters have moved, where necessary, from the smooth bookish language to the lively colloquial speech. Here is a couple of simple at first glance examples.

Original text:

— Здравствуй, Петрович!

— Здравствовать желаю, судырь, — сказал Петрович.

From the working correspondence:

Энья, обрати, пожалуйста, внимание на то, что слово «сударь» Петрович произносит как «судырь». Таким образом Гоголь через речь персонажа ещё раз напоминает читателю происхождение Петровича. Поэтому, «судырь» и ''sir'' плохо, слабо. Я думаю, что в английском соответствия, скорей всего, нет, но может быть, ты что-то предложишь?

I understand! So Petrovich is pronouncing it differently to the standard pronunciation? We could introduce a bit of what’s considered a ‘regional’ accent in the UK – I can’t think of a way to change ‘sir’ in a way that would reflect a different accent, but we could say “'Ow do ya do, sir”? Dropping the ‘h’ at the start of a word is very common in a lot of UK accents <…> and writing ‘ya’ instead of ‘you’ reflects a lot of these accents too, so it would be generic but definitely reflect a regional twang.

Translation:

“How are you doing, Petrovich?”

“ʼOw do ya do, sir,” said Petrovich.

And this is how the watchman speaks, using a French borrowing in his speech:

Original text:

«Чего лезешь в самое рыло, разве нет тебе трухтуара?»

From the working correspondence:

Здесь будочник произносит слово неправильно – «трухтуар», вместо правильного «тротуар». (Так же, как Петрович произносил «судырь» вместо правильного «сударь»). Будочник произносит его строго и важно, т.к. «тротуар» на то время было новомодным заимствованием из французского языка. Правильно выговаривать это слово будочнику непривычно. И звучит потешно.

I’m going to have a think on this as I work on these pages and try to come up with an adequate solution!

And Enya has found the solution!

Translation:

“Why are you getting right up in my mug, is the pavement not big enough for your derrière?”

For my better understanding, Miss Lennon explained her surely brilliant solution:

''English doesn’t have a French borrowing for the word “pavement”, so in cases where the literary choice cannot be replicated directly in the target language, one tactic can be to replicate it elsewhere in the sentence. This preserves the style in as close a way as possible and conveys any meaning, while ensuring that the target remains readable. So here, the important thing wasn’t necessarily the rendering of the word “pavement”, but the French borrowing. And, luckily, English makes use of the perfect one.''

The French borrowing "derrière" – buttocks. Ha! Which is also conveniently usually pronounced in a very English accent. How emotionally exact this character sounds now. By the way, Miss Lennon, in addition to Russian, speaks French also.

So, step by step, we "convinced" the characters of the story to speak English in a qualitatively different way, but just as naturally as they do it in the original work.

It is known that the English sentence has rather fixed word order if compared to Russian’s rather more mobile approach. The use of possibly flexible syntax where justified also offered a valuable sense of more accurately conveying the author's style.

It should be noted that the translator does not seek to ensure that their translation corresponds to the original work in terms of volume. On a book page of the same format where there are, say, twenty lines in the original, in the translation there can be two or three more or, in some cases, less.

But in our work, page-by-page correspondence in terms of volume and content is mandatory. This ensures the implementation of the unique, to say the least, feature of the bilingual books of the "Language through Reading" series – the possibility to read texts simultaneously in Russian and English. And so the texts in the books of the series are placed on a spread, where on the left, on an even page, is the source, and on the right, on an odd one, is its literary translation. Thus, the reader can see the text in two languages at the same time.

Bilingual reading is an effective technique for learning a foreign language and has a number of important features. The presence of the original and its literary translation in front of your eyes minimises the need to use a dictionary, which saves time and does not distract you from reading. This contributes to accelerated vocabulary acquisition and makes works easier to remember. All of these features ensure bilingual reading works well to develop a sense of language, and promotes freedom of speech by allowing a clearer and more precise expression of one's thoughts.

All together it works effectively

A year has flown by...

пн, 11 апр. 2022 г., 20:20

Hi Yuri!

<….>

How exciting that our translation is finished at last. Hopefully people will enjoy reading it. I've become very fond of Akakiy Akakievich over the last year. <….> …it was a great idea…<….>!

Best wishes,

Enya

* described by one American critic – Carl Ray Proffer (1938-1984) literary critic, translator of Russian literature, publisher, professor at the University of Michigan.